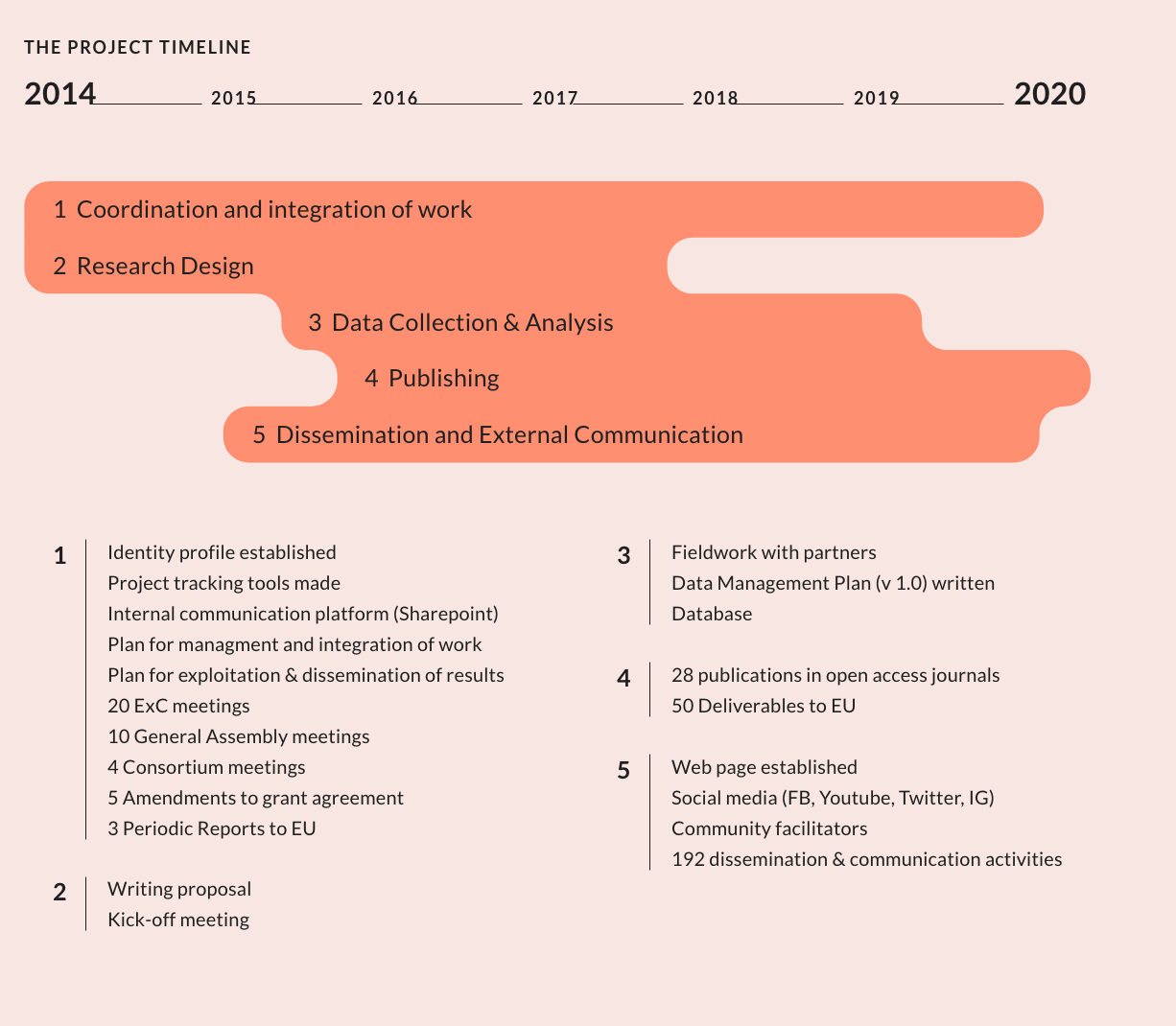

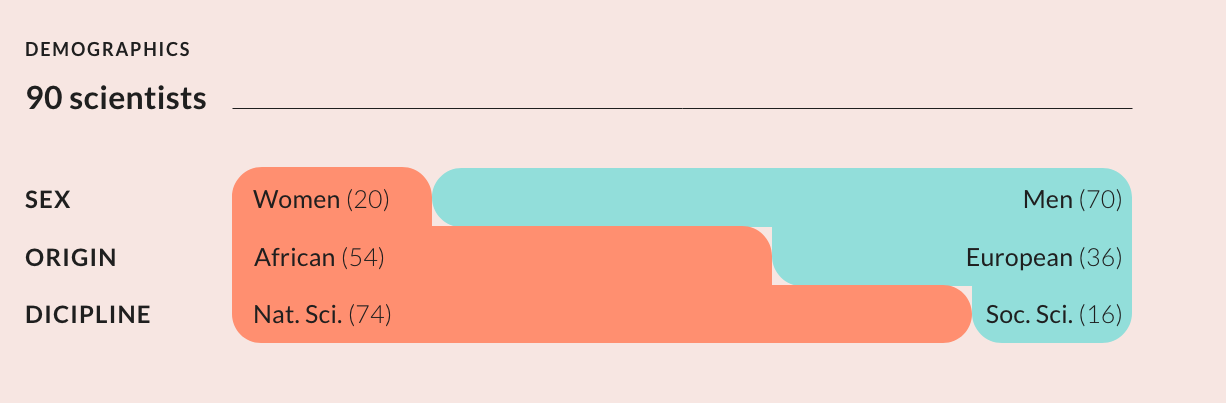

This text is one of the outcomes of a unique research project, AfricanBioServices, set in the Greater Serengeti-Mara Ecosystem of Tanzania and Kenya in East Africa. 4 years, €9.8 million. 7 African institutions (1). 6 European institutions (2). 91 researchers. 65 graduate degrees were funded over the course of the project, and nearly half of these were earned by African students. African and European students educated through AfricanBioServices have acquired early career exposure to international and interdisciplinary conservation research, setting the stage for new norms and innovations in science. In an effort to document and support the interdisciplinary and international cooperation represented in AfricanBioServices, this text emerged from the question—How would you advise future conservation scientists to approach interdisciplinary research with collaborators from diverse backgrounds? The primary audience for the text are students and researchers who work or intend to work in interdisciplinary and international conservation research projects such as AfricanBioServices. The hope is that it will be useful for class reading, workshops, and a companion during fieldwork.

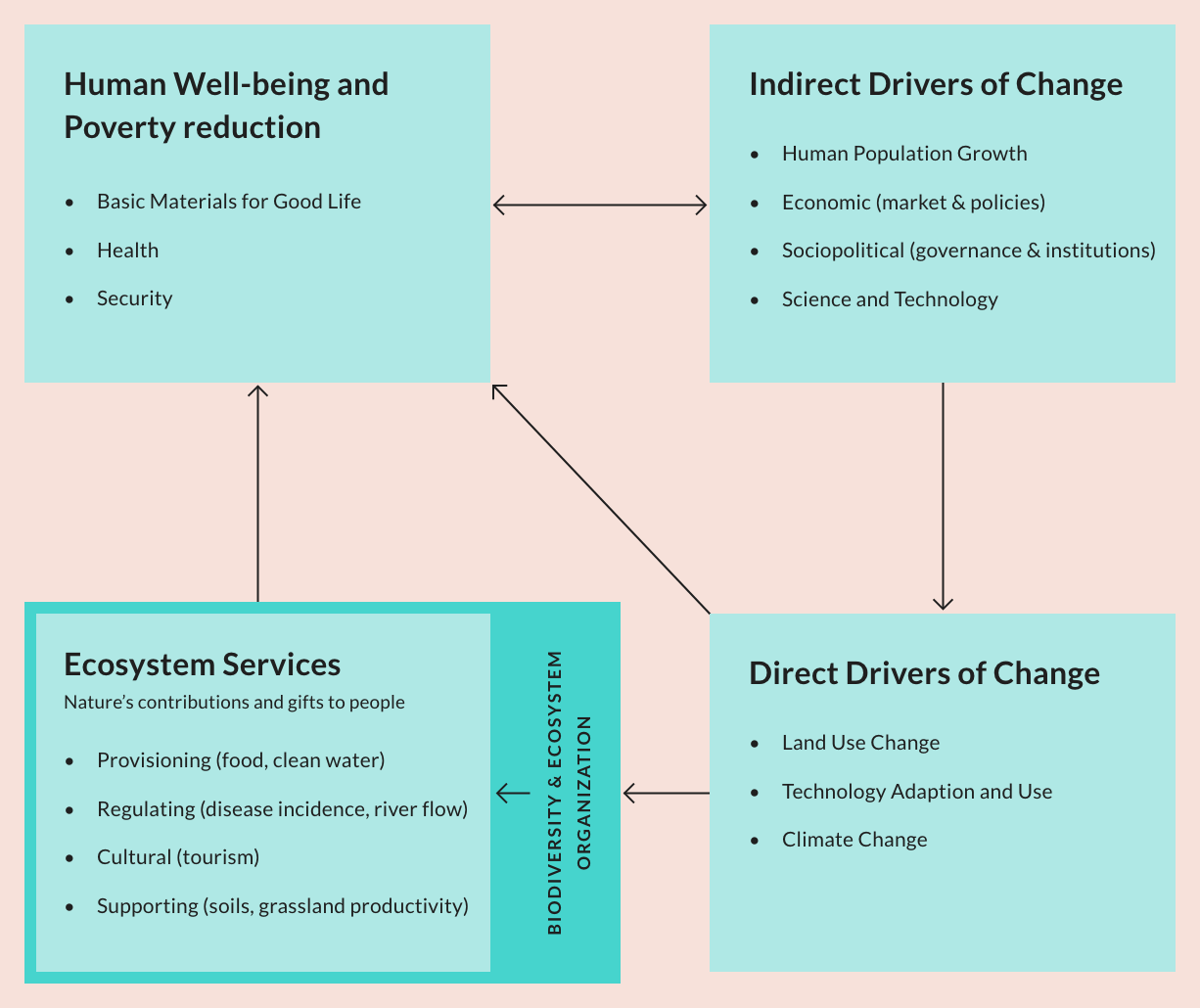

The AfricanBioServices project is an EU-funded research project that occurred from 2015-2019. This African-European scientific network conducted research under the project title “Linking Biodiversity, Ecosystem Functions and Services in the Serengeti-Mara Region, East Africa: Drivers of Change, Causalities and Sustainable Management Strategies.” The main aim of the project was to understand changes to biodiversity and ecosystem services in the GSME. Specifically, scientists studied the impacts of climate change, human population growth, and land use change on biodiversity and human well-being. Figure 1 illustrates the broad contours of the framework, which was informed by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment.

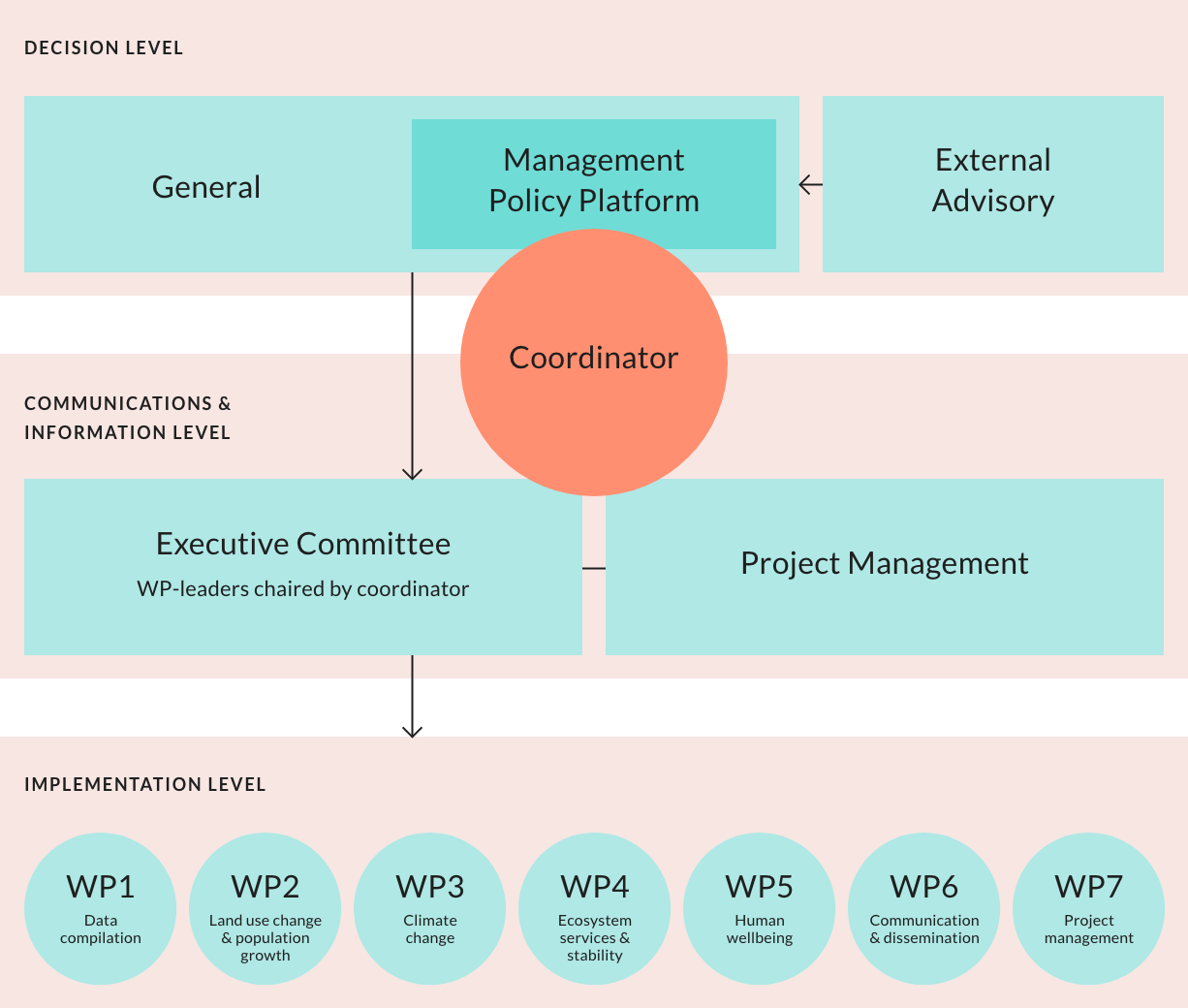

AfricanBioServices is organized into seven interlinked work packages (WPs) as illustrated in Figure 2. WP1 was responsible for assembling and integrating the relevant data from Kenya and Tanzania to create a regional picture. In WP2, the connections between human population growth, land use change and biodiversity changes are quantified. WP3 analysed the consequences of climate change for key aspects of biodiversity in the region. WP4 focused on the links between biodiversity and ecosystem organization, particularly the core ecosystem services on which people in the region depend. WP5 worked to quantify the dependence of human livelihoods on these ecosystem services and evaluate management options. The central focus of WP6 was to initiate innovative ways for communicating and disseminating the results of the project through a forward-thinking strategy of ‘continuous engagement’ with local stakeholders that has a proven track record of success. WP7 encompasses the project management and aims at achieving the objectives and milestones in a timely manner and to the highest possible standards.

AfricanBioServices was ground-breaking symbolically and substantively. It represented an innovative attempt at knowledge exchange between African and European conservation researchers from across disciplines. It was also extraordinary in the amount and quality of data collected, the impact of publications produced, and the resources transferred to African conservation institutions. This was possible, in part, due to the international and interdisciplinary cooperation that bloomed during this project, and this is the subject of this text. The aim is to share important insights about best practices to keep in mind as scientists engage in the research process with an interdisciplinary and international group of collaborators. The hope is that this text prompts discussion as opposed to presenting a definitive answer to addressing the dynamic issue of conservation research as a social process. The text emphasises an approach to social relationships among scientists having temporal, intertwined, and processual dimensions. Through this approach, taboo topics in scientific research are also unearthed.

While scientific rigor is the ultimate goal of research, the pursuit of this goal is influenced by the social context in which it is pursued. Science has universal aims as well as local dimensions. Where and with whom you work influence the process and outcome of the work. These processes have historical contexts and cultural dimensions that influence the relationships between scientists as well as the relationships between scientists, governments, and communities. This text attempts to take on these complex matters by letting scientists address it in their own words. Above all else, the text tries to be accessible to an audience who is as diverse as the group who helped produce it.

AfricanBioServices was exemplary in terms of the representation of African scientists and junior scientists. In terms of gender and representation of social scientists, the project was lacking. Gender representation among African partners was better than European institutions. Among graduate students, gender was a bit more balanced. This could be perceived as an artefact of changing academic norms, which is a partial explanation. It also reveals the continued attention and action that is required to have full social inclusion. The illustrations below give an overview of the demographic makeup of the project. The Book Contributors section portion of the text provides photographs and details of the project members who are quoted in this text.

The title—One Field Guide: Navigating the Social Context of Conservation Research—encompasses a number of dimensions of the text. “One” is intended to suggest that this is an approach, not the approach. The best practices of a discipline should be transferrable, and the hope is that this text has relevance for conservation research projects in other parts of the world. However, is does not seek to be hegemonic in its recommendations. The analytic posture strives to be open-minded, with the goal of continually refining the research process through reflection. In this case, a reflective stance has generated two major findings. First, the social context of scientific projects can be understood through the three themes: cooperation, context, and communication. Second, these three themes—the 3Cs—are heavily intertwined and change in significant ways over the lifetime of the project.

This is but one response to the dynamic issue of interdisciplinary, international research, which is an issue that is beginning to gain the interest and attention that it deserves. We hope other practical approaches to managing the social context of research will find this to be an important contribution to this broader conversation and useful to build upon. We hope to hear critiques about what we have tried to accomplish. Challenges and critiques are not seen as final and instead as opportunities to go deeper, learn more, and improve.

We look forward to hearing feedback from a diverse audience of readers in our effort to contribute to preparing the next generation of scientists from around the world to work together.A dynamic, pluralistic, and open-minded approach is required to truly participate in projects that bring together different perspectives towards the common goal of sustainability. This is reflected in the understanding that there is not one singular approach.

“Field Guide” is a play on the common genre of text that is used by wildlife scientists to identify plants and animals. Calling this text a guide connotes that another sort of guidance is needed in the field beyond the capacity to identify species (though this core competency for ecologists remains extremely important). This text compiles this other type of guidance by presenting the insights of African and European scientists. The purpose is to share their experiences so that best practices can be created, debated, and abided by during international and interdisciplinary conservation research.

Science, like many intellectual endeavours that passed through colonial institutions, is fraught with the norms and legacy of the Scramble for Africa. Addressing this historical inequality through science with the aim of more rigorous and fair research is a goal of international and interdisciplinary science. This dynamic and important pursuit ought to be fully embraced by the global conservation community. The hope is that conservation research will become a model of international cooperation. If not, conservation could become a bastion of international competition

Furthermore, conversations about inclusion in conservation research must be transformed into action. This term “guide” is also intended to mark that this is a living document that needs to be taken into the field and revised as new understandings emerge. It is to be used in the field to ensure that it is a living document, subject to change and context. A guide presents common knowledge so that it can be easily applied to observations. In this way, a guide is both theoretical and applied. Like a guide, it is to be a living document.

The guide was created to be used by a variety of scientific audiences as they develop and maintain best practices for international and interdisciplinary research on social-ecological systems. It can be used as a weekly reading for a conservation course or during conferences, workshops, and project meetings about conservation. The guide is intended to inspire further dialogue by encouraging conservationists to think further about the social aspects of conservation research prior to, during, and after field research. The quotes that have been selected from interviews with scientists are intended to be both informative and inspiring.

The guide can be used in its entirety or in sections. It can be read chronologically from or thematically. Due to this structure, it can also be read in its entirety as coursework or leafed through for intellectual enjoyment. The guide is also intended to connect to other important initiatives to improve conservation, such as the European environmental research and innovation policy (Europe 2020, Lisbon Strategy), the Global Biodiversity Agreement (under UN biodiversity convention), the IPBES reports, and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Many of these initiatives rely upon and mandate collaboration as an integral part of conservation and this guide could be useful to those assemblies.

The four core chapters reflect the phases of the research process that occur over the lifetime of a scientific project. Each of the four core chapters (Research Design, Data Collection & Analysis, Publishing, and Dissemination & External Communication) is structured similarly. The chapters open with an introduction that is followed by a series of quotes organized by theme—Context, Cooperation, and Communication—the 3Cs. Each of the four chapters concludes with questions that can be discussed in groups of individuals or groups of teams.

The quotes were gleaned from researchers and research assistant who worked on the AfricanBioServices project about executing these four aforementioned phases of research in dynamic interdisciplinary and international research collaborations. The quotes are transcribed portions of structured and semi-structured interviews with scientists. In some cases, scientists submitted their responses in writing. After analysing the quotes for key ideas, a thematic framework was crafted. This framework is one of the findings of this text and is comprised of three themes that help to organize, interpret, and link the quotes. The three themes are Context, Cooperation, and Communication.

These three themes are used to organize the quotes from scientists throughout the four core chapters to demonstrate the relevance and importance of these three dimensions to each phase of research. The use of quotes and the digital format of the guide are efforts to increase its accessibility and mobility. This approach aims to provide an organizational structure that presents scienists in their own voices. The aim is to highlight that science is produced by individuals who have diverse perspectives and complex social relations. There are many points of consensus and disagreement revealed in the quotations, highlighting the ongoing social and political nature of scientific production.

The three organizing themes—Context, Cooperation, and Communication—are understood as social dimensions of research. These dimensions of research offer a way of framing the ways in which social relations impact a research endeavour. Context is a reminder to pay attention to temporal and spatial surroundings as socially constructed through relationships, institutions, processes, and history that are broader than that temporal and spatial context. The factors that influence a person or place are broader than what is evident in the immediate present. For instance, an understanding of the past is needed to understand the present. Furthermore, interdisciplinary and international perspectives work to ensure that a broad set of variables and indicators are being considered. Observations, however seemingly straightforward, must be interpreted contextually.

Cooperation is essential in developing and maintaining research collaborations that are mutually beneficial, particularly for those who pay the cost of maintaining conservation areas and caring for wildlife. Evolutionary theory struggles to explain cooperation in humans, and humans struggle to maintain cooperative mind-sets and relationships in the real world. Yet, human beings rely heavily on the joint pursuit of goals. Cooperation, at the very least, requires an awareness of the costs and benefits for cooperative partners. To understand the costs and benefits from another person’s perspective, one must listen to others. Listening must be active and attentive. One must pause their agenda and listen for understanding. Asking thoughtful questions is a good indication of listening and a sign of good cooperation. It is also important to share honest expressions of your positions as well. This, too, is aided by listening. People are more likely to listen to you, if you listen to them. If someone is not listening to you, perhaps it is because they feel as though you are not listening to them. In order to achieve a cooperative agenda and maintaining a cooperative agenda, listening and communication are essential.

Communication is the third dimension that ought to be a constant concern throughout each stage of research. There are many forms of communication and many audiences that come together in international and interdisciplinary research projects. Humans with different languages, scholars with different backgrounds, institutions with different agendas, and animals with different capacities are all sending out signals, signs, and other forms of communication in conservation research. Identifying the modes of communication and the message embedded in the communication is one aspect. It is important to understand what is said as well as unsaid in the production of scientific research. The interpretation of communication often requires translation and a sensitivity to who has the power to include or exclude messages.

The awareness of taboo subjects in science is one of the central insights of using these three themes to synthesize meaning from the quotes. An awareness of time as a social dynamic in the research process also emerges as a central insight. The interconnected nature of the three themes and the phases of research also become apparent. The open-mindedness needed to remain aware of shifts over time and interconnectivity of collaboration is also helpful in addressing the taboos of scientific production. Here, we see the multiple benefits of using a structured and adaptive approach such as the 3Cs.

Although the 3Cs approach emerged through reflective analysis about AfricanBioServices, the organizational structure of AfricanBioServices was also designed with social context in mind. In this way, the themes of cooperation, communication, and context may have emerged through the design. A number of specific tools were developed to address what was understood, both implicitly and explicitly, about the social context of the AfricanBioServices project. For instance, cooperation was evident in the various platforms for discussion among project participants. Each year of the project, an annual meeting was convened in an African location where scientists, policy makers, and people who live in the GSME met to discuss findings and issues. The inclusion of policy makers and people who live in the GSME demonstrates an appreciation of context. An appreciation of context is also reflected in the important role of scientists from Kenya and Tanzania in shaping the project at various phases. A commitment to communication is detailed in the project’s Plan for Exploitation and Dissemination of results as well as the Data Repository and Management Plan. The creation of this text was also detailed in the project plan and is an example of project plans to document reflections from the project.

The social dynamics that influence a research collaboration are often examined as the project comes to a close or in hindsight. The social dynamics of a research collaboration, particularly among a diverse group in a post-colonial context, should be considered from the beginning of a project and be continually discussed. Time allocation and time management are complicated tasks when taking on collaborative work with tangible outputs. Discussing the understanding of communication, cooperation, and context throughout a research project should be prioritized. It can often help avoid significant issues that impact the scientific output.

Think back on a productive and a failed professional relationships and the degree to which they can be better understood through an appreciation of context, cooperation, and communication. The 3Cs can act as an analytical lens to guide your actions as you navigate research collaborations. The social context of research projects has often been overlooked or seen as secondary by conservation scientists but it is always relevant. Wherever research is present, communication, cooperation, and context come to bear. This is a posture that more scientists need to become more comfortable occupying and that many successful scientists understand.